The main obstacle to a more fruitful relationship with the United States is overcoming the mistrust that still prevails, on both sides.

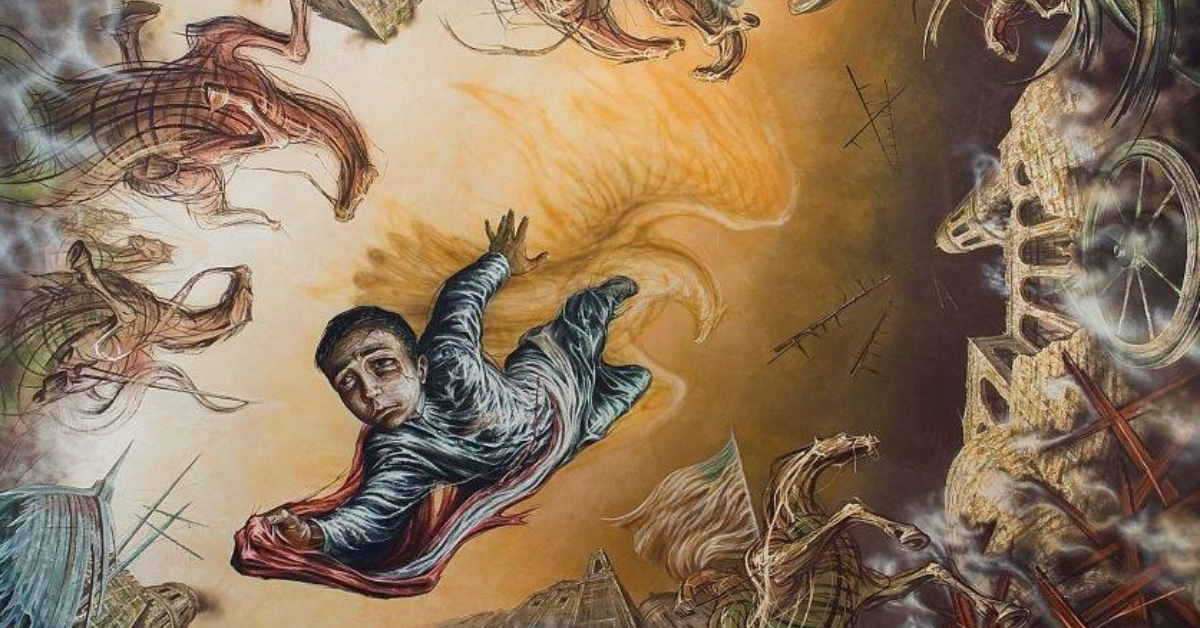

Opinion by Eduardo Guerrero Gutierrez: On the main stairs of the Chapultepec Castle you can see The Sacrifice of the Children Heroes, by the Jalisco painter Gabriel Flores García. It is an impressive and moving work. In the background, an army, spectral and menacing, wave the banner of stars and stripes. At the center of the mural, the face of the young cadet who throws himself . . .