The overhaul of Mexico’s banking laws, enacted as part of President Enrique Peña Nieto’s wide-ranging economic and business structural changes, is designed to increase credit to small and medium-sized businesses while enhancing regulatory oversight and transparency.

Promises of wide-ranging structural reforms aimed at boosting long-run growth and economic development accompanied Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto’s arrival in office in December 2012.

Changes have followed, including legislative approval of plans to modernize important sectors of the economy, most notably a constitutional amendment ending state monopolies over oil and gas as well as . . .

CONTINUE READING THIS NEWS ARTICLE BY BECOMING A PVDN SUBSCRIBER!

>> SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWS ON WHATSAPP CHANNELS HERE (FROM YOUR CELL PHONE!)<<

Popular posts:

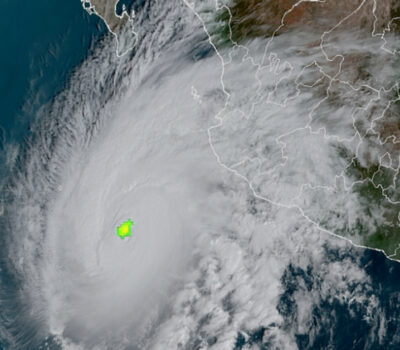

Mexican Navy Secretariat Releases 2024 Hurricane Season Forecasts Puerto Vallarta, Mexico - As the 2024 hurricane season approaches, anticipation and concern linger about the potential impact of these powerful natural phenomena. In response to these inquiries, the Secretary of the Navy (Semar) of Mexico has unveiled its forecasts, shedding light on what the upcoming season may entail. Season Commencement: The initiation of the…

Mexican Navy Secretariat Releases 2024 Hurricane Season Forecasts Puerto Vallarta, Mexico - As the 2024 hurricane season approaches, anticipation and concern linger about the potential impact of these powerful natural phenomena. In response to these inquiries, the Secretary of the Navy (Semar) of Mexico has unveiled its forecasts, shedding light on what the upcoming season may entail. Season Commencement: The initiation of the… Get to Know Puerto Vallarta’s Most Traditional Beach Snack Puerto Vallarta, Mexico - Strolling along Puerto Vallarta's sandy stretches, one can't help but be enticed by the offerings of beachside vendors. From the comforting aroma of banana bread to the zesty allure of mangoes with chamoy, the options are as diverse as they are delectable. But amidst this cornucopia of treats, there's one delicacy…

Get to Know Puerto Vallarta’s Most Traditional Beach Snack Puerto Vallarta, Mexico - Strolling along Puerto Vallarta's sandy stretches, one can't help but be enticed by the offerings of beachside vendors. From the comforting aroma of banana bread to the zesty allure of mangoes with chamoy, the options are as diverse as they are delectable. But amidst this cornucopia of treats, there's one delicacy… Citizens of Puerto Vallarta Still Feel Safe Putting The City in Seventh Place in the Country Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco, continues to shine as one of Mexico's safest cities, securing its position among the nation's top 10 cities where citizens feel most secure, according to the latest National Urban Public Safety Survey (ENSU) conducted by INEGI. The survey, which evaluates citizen perceptions of safety, covers the first quarter of the year and…

Citizens of Puerto Vallarta Still Feel Safe Putting The City in Seventh Place in the Country Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco, continues to shine as one of Mexico's safest cities, securing its position among the nation's top 10 cities where citizens feel most secure, according to the latest National Urban Public Safety Survey (ENSU) conducted by INEGI. The survey, which evaluates citizen perceptions of safety, covers the first quarter of the year and… Viva Aerobús Expands Air Routes, Including New Connection to Puerto Vallarta Puerto Vallarta, Mexico - To bolster connectivity and cater to the burgeoning demand for air travel, Viva Aerobús, a prominent Mexican low-cost airline, has announced the introduction of seven new national routes originating from the Felipe Ángeles International Airport (AIFA). Among these freshly unveiled destinations stands Puerto Vallarta, a popular resort city on Mexico's Pacific…

Viva Aerobús Expands Air Routes, Including New Connection to Puerto Vallarta Puerto Vallarta, Mexico - To bolster connectivity and cater to the burgeoning demand for air travel, Viva Aerobús, a prominent Mexican low-cost airline, has announced the introduction of seven new national routes originating from the Felipe Ángeles International Airport (AIFA). Among these freshly unveiled destinations stands Puerto Vallarta, a popular resort city on Mexico's Pacific… Price of Gasoline in Puerto Vallarta is the Most Expensive in Mexico Puerto Vallarta, Mexico - During the weekly update of the Federal Consumer Prosecutor's Office (Profeco) on Monday, April 15, David Aguilar, the head of the agency, highlighted concerning trends in fuel prices in Jalisco. Aguilar pointed out that in the state, particularly in Puerto Vallarta, citizens are grappling with exorbitant rates for both premium and…

Price of Gasoline in Puerto Vallarta is the Most Expensive in Mexico Puerto Vallarta, Mexico - During the weekly update of the Federal Consumer Prosecutor's Office (Profeco) on Monday, April 15, David Aguilar, the head of the agency, highlighted concerning trends in fuel prices in Jalisco. Aguilar pointed out that in the state, particularly in Puerto Vallarta, citizens are grappling with exorbitant rates for both premium and… Puerto Vallarta Gears Up for the 2024 Marathon Puerto Vallarta is abuzz with anticipation as it braces to host the fifth edition of its renowned Marathon, slated to kick off on April 21. This eagerly awaited sporting spectacle has firmly entrenched itself as a highlight on the global athletic calendar, drawing participants from diverse corners of the world. The 2024 Puerto Vallarta Marathon…

Puerto Vallarta Gears Up for the 2024 Marathon Puerto Vallarta is abuzz with anticipation as it braces to host the fifth edition of its renowned Marathon, slated to kick off on April 21. This eagerly awaited sporting spectacle has firmly entrenched itself as a highlight on the global athletic calendar, drawing participants from diverse corners of the world. The 2024 Puerto Vallarta Marathon… Cultural Clash: Complaints of Noise by Expats Spark Debate Across Mexico Puerto Vallarta, Mexico - In Mexico, the vibrant tapestry of culture is woven with the threads of music, celebration, and tradition. However, recent complaints from expatriates, primarily of American origin, have sparked a debate on the intersection of cultural identity and noise pollution. Mazatlán's Sinaloan Band Protest In late March, the boardwalks of Mazatlán, Sinaloa,…

Cultural Clash: Complaints of Noise by Expats Spark Debate Across Mexico Puerto Vallarta, Mexico - In Mexico, the vibrant tapestry of culture is woven with the threads of music, celebration, and tradition. However, recent complaints from expatriates, primarily of American origin, have sparked a debate on the intersection of cultural identity and noise pollution. Mazatlán's Sinaloan Band Protest In late March, the boardwalks of Mazatlán, Sinaloa,… Pride Pet Parade Returns to Puerto Vallarta for Second Consecutive Year Puerto Vallarta, Mexico - On May 20, 2024, Puerto Vallarta will once again embrace its furry companions and their human counterparts as the PV Pride Pet Parade returns for its second edition. This vibrant event, dedicated to celebrating the bond between pets and their guardians, will grace the Malecón of Puerto Vallarta at sunset, promising…

Pride Pet Parade Returns to Puerto Vallarta for Second Consecutive Year Puerto Vallarta, Mexico - On May 20, 2024, Puerto Vallarta will once again embrace its furry companions and their human counterparts as the PV Pride Pet Parade returns for its second edition. This vibrant event, dedicated to celebrating the bond between pets and their guardians, will grace the Malecón of Puerto Vallarta at sunset, promising… Triple Arrival of Cruise Ships Brings Thousands of Tourists to Puerto Vallarta Puerto Vallarta, Mexico - On Tuesday, April 16th, Puerto Vallarta witnessed a bustling spectacle as three grand cruise ships made their way into its vibrant harbor, injecting the city with a surge of international tourists eager to explore this renowned beach destination. The trio of maritime giants included the Zaandam, gracefully docking at Pier 1,…

Triple Arrival of Cruise Ships Brings Thousands of Tourists to Puerto Vallarta Puerto Vallarta, Mexico - On Tuesday, April 16th, Puerto Vallarta witnessed a bustling spectacle as three grand cruise ships made their way into its vibrant harbor, injecting the city with a surge of international tourists eager to explore this renowned beach destination. The trio of maritime giants included the Zaandam, gracefully docking at Pier 1,… Here’s Why Mexico Tops Global Retirement Index 2024: A Haven for International Pensioners In the quest for tranquility and life's pleasures, Mexico emerges as the top choice for international pensioners, according to the Annual Global Retirement Index 2024. This designation, propelled by the preferences of the Baby Boomer generation, born between 1946 and 1964, underscores the nation's appeal as a refuge offering mild climates and diverse natural landscapes.…

Here’s Why Mexico Tops Global Retirement Index 2024: A Haven for International Pensioners In the quest for tranquility and life's pleasures, Mexico emerges as the top choice for international pensioners, according to the Annual Global Retirement Index 2024. This designation, propelled by the preferences of the Baby Boomer generation, born between 1946 and 1964, underscores the nation's appeal as a refuge offering mild climates and diverse natural landscapes.…