Currently, most of the marijuana consumed in the United States is produced within its borders, due to the ongoing legalization and decriminalization processes in several of its states.

This has hit Mexican organized crime groups and increased the prices of marijuana in Mexico. However, the InSight Crime organization found that drug traffickers have found new strategies to expand their markets.

The investigation “The end of (illegal) marijuana: what it means for criminal dynamics in Mexico”, published this Wednesday, delves into how the legalization of marijuana in the US is impacting organized crime.

The experts conducted interviews in Baja California, Sinaloa, and Mexico City with cannabis growers, farmers, businessmen, state and federal government officials, marijuana users, activists, security experts, and academics, among others.

They also visited several dispensaries and former production centers, while analyzing government data on drug seizures and consumption trends, court cases, and previous studies on the subject.

With this, they found that marijuana is no longer a priority for the authorities, which is why its seizures at the border and in Mexico have steadily decreased over the last decade. Similarly, the Mexican army eradicates fewer plantations each year.

Instead, the government is increasingly focusing on the trade in synthetic drugs, which are rapidly replacing those of plant origin.

The illicit marijuana business is declining due to legalization in the US, as demand has dwindled. In 2006, a kilogram of low-quality marijuana was sold in Mexico for about 800 pesos, or $40. Today, that same kilogram is sold for around a third of that price.

Faced with falling prices, groups like the Sinaloa Cartel have moved towards producing and exporting synthetic drugs. With this, they have stopped depending on farming communities to harvest illicit crops, from those who previously produced cannabis.

As a result, rural people who traditionally grew marijuana are migrating to other crops or government-funded development programs or looking for ways to enter the legal business of selling this drug.

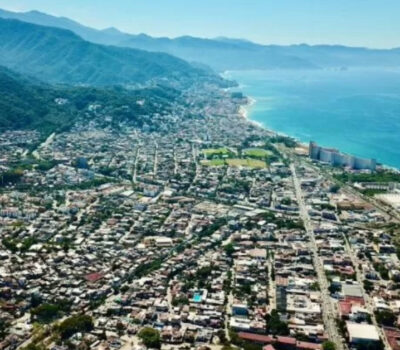

Likewise, they have ventured into delivery jobs or become truckers in other major cities such as Culiacán, Los Mochis, and Mazatlán.

However, these inhabitants still live under the constant threat of violence from criminal groups. Still, they no longer derive the kind of economic benefits they once received from the drug trade, the research argues.

In contrast, criminal groups have adapted to these changes and have diversified their operations to capitalize on new markets. In addition, they now dominate the synthetic drug trade in the United States, which generates more income for them.

Likewise, sales of cannabis in legal US states are spreading to places where it is still illegal, while Mexican drug traffickers are looking to capitalize on the local consumer market in Mexico.

This has also created greater threats to farm workers, truck drivers, and others who work long hours for little pay. For them, the use of cheap synthetic drugs, especially methamphetamine, has become part of their routine.

Methamphetamines are now one of the most abused drugs and an increasing number of people are seeking treatment for the use of fentanyl, according to data from the Mexican Observatory of Mental Health and Drug Consumption.

The investigation details that in Culiacán, Sinaloa, there are at least 18 informal marijuana dispensaries, where drugs are sold that can be paid with Mexican pesos, US dollars, bank transfers, and even Bitcoin.

In addition to stores like these, Ovidio Guzmán López, Iván Archivaldo, and Jesús Alfredo Guzmán Salazar have a firm grip on the street sale of drugs in Culiacán.

Together they are known as the Chapitos. The three are the children of Joaquín Guzmán Loera, alias “El Chapo”, the former leader of the Sinaloa Cartel, who is now imprisoned for life in a maximum security prison in the United States.

For each son, the US government is now offering a $5 million reward to anyone who can provide information leading to his arrest in order to dismantle the criminal organization.

In the state in the north of the country, the Chapitos decide where and when the drugs should be moved. They also set the price at each step of the production chain, and select who to sell to and who not. People who do not follow these rules suffer the consequences, which can be fatal, notes InSight Crime.

In addition, El Chapo’s sons run a vast market in methamphetamine and fentanyl. Unlike marijuana, these do not require large tracts of land or a specific climate. Synthetic drug labs can operate anywhere there is electricity, water, and ventilation, the research explains.

The vast majority of this clandestine production is destined for consumers in the United States, but a growing part stays in major cities like Culiacán, where the Chapitos set the price.

Currently, most of the marijuana consumed in the United States is produced within its borders, due to the ongoing legalization and decriminalization processes in . . .