Fourteen Tzotzil families displaced by violence in Chenalhó call on Chiapas Governor Eduardo Ramírez for relocation, housing, and basic rights after nine years in precarious conditions.

More than a dozen Indigenous Tzotzil families, displaced from their homes by violence in the highlands of Chiapas, issued a renewed plea to the state government this week, calling for a “comprehensive relocation” after nearly a decade of living in makeshift shelters without basic services.

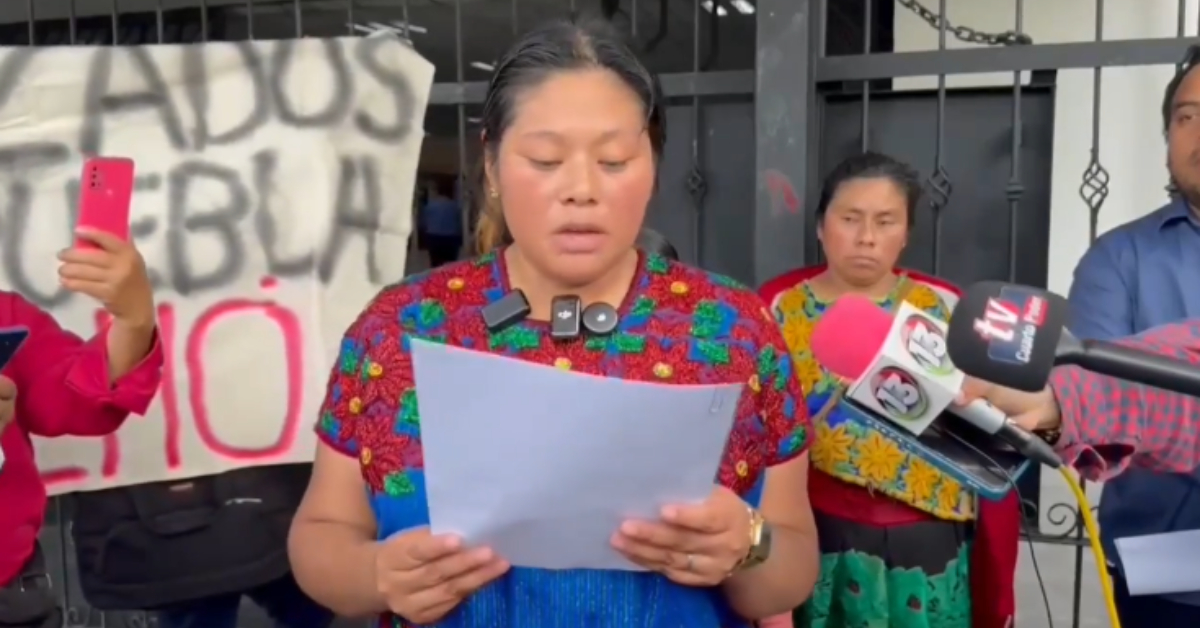

Araceli Cruz, spokesperson for the 14 displaced families, addressed the media on Monday in San Cristóbal de las . . .