Tourism is a cornerstone of capital accumulation in Mexico, boasting impressive figures that underscore its economic significance. Last year, the country welcomed over 42 million international tourists, nine million of whom arrived via cruise ships, generating a staggering revenue of $30.809 billion.

Since the mid-20th century, the Mexican government has actively promoted tourism, particularly in beach destinations. Acapulco in the 1940s, Puerto Vallarta in the late 1960s, and Cancún during the six-year term of President Luis Echeverría Álvarez (1970-1976) are prominent examples.

Notably, President Álvarez also initiated the Bahía de Banderas Trust, catalyzing tourism in what became Nuevo Vallarta in Nayarit state. The rhetoric surrounding tourism often champions it as the “industry without chimneys,” portraying it as an environmentally friendly and economically beneficial endeavor due to its job creation and economic prosperity.

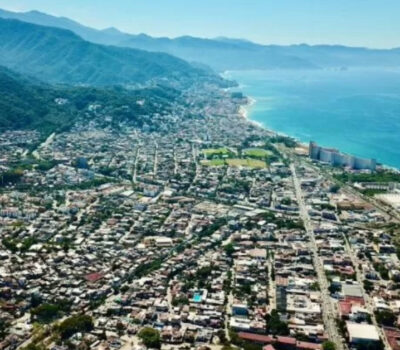

In Jalisco, tourism plays a pivotal role, with Puerto Vallarta standing out as a gem in the state’s tourist crown. The picturesque coastal town, home to just over 220 thousand residents, hosted over six million tourists last year alone, generating a revenue of 41.322 billion pesos.

However, beneath the veneer of economic prosperity lie concerns and unintended consequences associated with tourism. In recent years, the term “tourism” has garnered attention from academics and the media, highlighting its negative externalities and adverse impacts worldwide. Cities like Paris, Barcelona, and Venice have grappled with the repercussions of mass tourism, including the erosion of local culture, population displacement, soaring rents, and housing shortages.

The undesirable effects of tourism have prompted UNESCO to issue warnings, with Venice facing the threat of being listed as a heritage site in danger due to mass tourism and climate change impacts. Voices from affected communities, such as a Venetian quoted by DW, express frustration and plea for tourists to refrain from visiting, citing the degradation of cultural experiences.

Similar concerns are now echoing in Puerto Vallarta. According to environmental journalist Alejandra Valenciano, the influx of tourism has sparked criticism and apprehension regarding its impact on the city. New consumption patterns and the influx of foreigners into central neighborhoods like Versalles and the Romantic Zone have driven up housing prices and displaced local residents. This phenomenon, termed “touristification” or “Venice syndrome,” reflects the imposition of economic, labor, and social dynamics that often prioritize tourism interests over those of the resident population.

Research by scholars from the University Center of the Coast of the UdeG reveals troubling findings, including modifications to urban planning that prioritize real estate development and the erosion of state regulatory powers in favor of private sector interests. These findings challenge the prevailing discourse touting the benefits of tourism, urging a critical examination of its adverse effects.

In light of these complexities, it is imperative to engage in nuanced discussions that acknowledge both the economic opportunities and the social costs associated with tourism.

The above article is written by author Rubén Martín and originally appeared in Spanish on Informador

Tourism is a cornerstone of capital accumulation in Mexico, boasting impressive figures that underscore its economic significance. Last year, the country welcomed over 42 million international tourists, nine million of whom arrived via cruise ships, generating a staggering revenue of $30.809 billion.

Since the mid-20th century, the Mexican government has actively promoted tourism, particularly in beach destinations. Acapulco in the 1940s, Puerto Vallarta in the late 1960s, and Cancún during the six-year term of President Luis Echeverría Álvarez (1970-1976) are prominent examples.