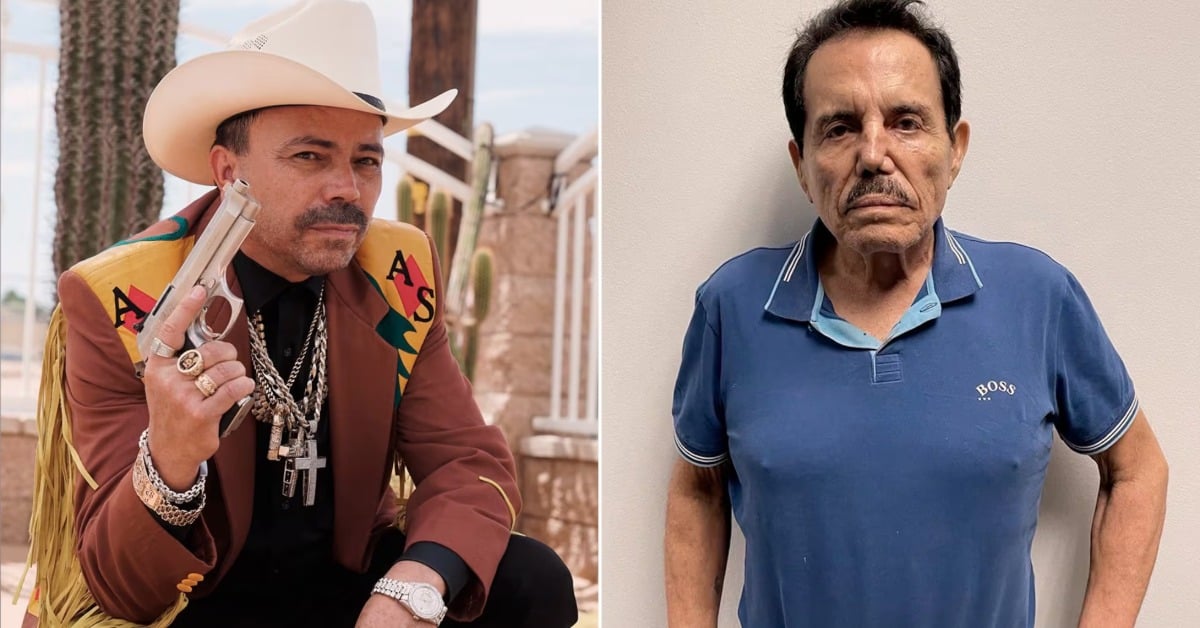

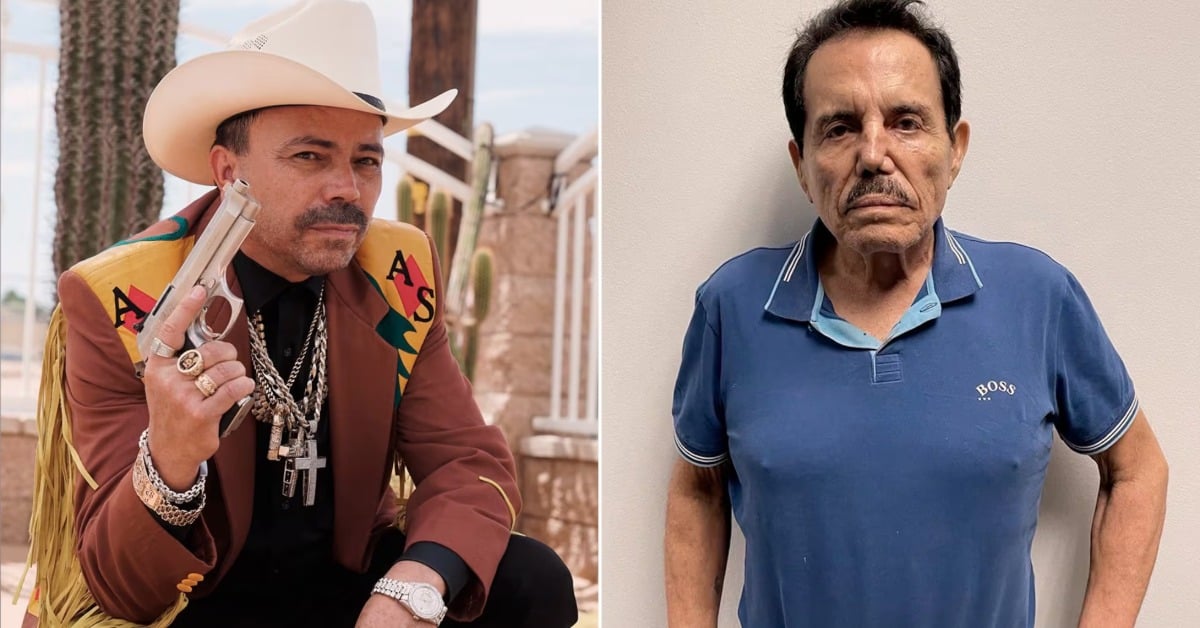

The U.S. Justice Department will not pursue the death penalty against top Mexican drug lords including El Mayo and Caro Quintero . . .

The U.S. Justice Department will not pursue the death penalty against top Mexican drug lords including El Mayo and Caro Quintero . . .