For a brief moment, it looked like Pixar had finally made history by offering up the first gay character in a Disney animated film. The Internet erupted last month over a new trailer for "Finding Dory" that showed two women next to a baby stroller that's attacked by an octopus. Some viewers wondered if they were a lesbian couple, as US Weekly and other entertainment outlets reported on the speculation. It would have been long overdue after 16 previous Pixar films had been populated exclusively by heterosexuals.

But according to our spies at an early screening, "Finding Dory" doesn . . .

CONTINUE READING THIS NEWS ARTICLE BY BECOMING A PVDN SUBSCRIBER!

>> SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWS ON WHATSAPP CHANNELS HERE (FROM YOUR CELL PHONE!)<<

Popular posts:

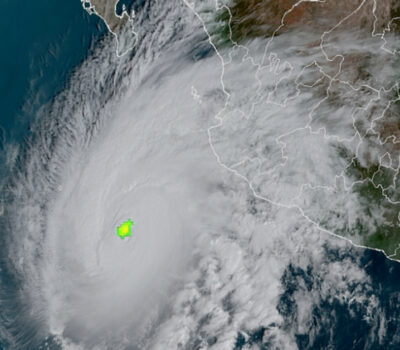

Mexican Navy Secretariat Releases 2024 Hurricane Season Forecasts Puerto Vallarta, Mexico - As the 2024 hurricane season approaches, anticipation and concern linger about the potential impact of these powerful natural phenomena. In response to these inquiries, the Secretary of the Navy (Semar) of Mexico has unveiled its forecasts, shedding light on what the upcoming season may entail. Season Commencement: The initiation of the…

Mexican Navy Secretariat Releases 2024 Hurricane Season Forecasts Puerto Vallarta, Mexico - As the 2024 hurricane season approaches, anticipation and concern linger about the potential impact of these powerful natural phenomena. In response to these inquiries, the Secretary of the Navy (Semar) of Mexico has unveiled its forecasts, shedding light on what the upcoming season may entail. Season Commencement: The initiation of the… Citizens of Puerto Vallarta Still Feel Safe Putting The City in Seventh Place in the Country Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco, continues to shine as one of Mexico's safest cities, securing its position among the nation's top 10 cities where citizens feel most secure, according to the latest National Urban Public Safety Survey (ENSU) conducted by INEGI. The survey, which evaluates citizen perceptions of safety, covers the first quarter of the year and…

Citizens of Puerto Vallarta Still Feel Safe Putting The City in Seventh Place in the Country Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco, continues to shine as one of Mexico's safest cities, securing its position among the nation's top 10 cities where citizens feel most secure, according to the latest National Urban Public Safety Survey (ENSU) conducted by INEGI. The survey, which evaluates citizen perceptions of safety, covers the first quarter of the year and… Viva Aerobús Expands Air Routes, Including New Connection to Puerto Vallarta Puerto Vallarta, Mexico - To bolster connectivity and cater to the burgeoning demand for air travel, Viva Aerobús, a prominent Mexican low-cost airline, has announced the introduction of seven new national routes originating from the Felipe Ángeles International Airport (AIFA). Among these freshly unveiled destinations stands Puerto Vallarta, a popular resort city on Mexico's Pacific…

Viva Aerobús Expands Air Routes, Including New Connection to Puerto Vallarta Puerto Vallarta, Mexico - To bolster connectivity and cater to the burgeoning demand for air travel, Viva Aerobús, a prominent Mexican low-cost airline, has announced the introduction of seven new national routes originating from the Felipe Ángeles International Airport (AIFA). Among these freshly unveiled destinations stands Puerto Vallarta, a popular resort city on Mexico's Pacific… Price of Gasoline in Puerto Vallarta is the Most Expensive in Mexico Puerto Vallarta, Mexico - During the weekly update of the Federal Consumer Prosecutor's Office (Profeco) on Monday, April 15, David Aguilar, the head of the agency, highlighted concerning trends in fuel prices in Jalisco. Aguilar pointed out that in the state, particularly in Puerto Vallarta, citizens are grappling with exorbitant rates for both premium and…

Price of Gasoline in Puerto Vallarta is the Most Expensive in Mexico Puerto Vallarta, Mexico - During the weekly update of the Federal Consumer Prosecutor's Office (Profeco) on Monday, April 15, David Aguilar, the head of the agency, highlighted concerning trends in fuel prices in Jalisco. Aguilar pointed out that in the state, particularly in Puerto Vallarta, citizens are grappling with exorbitant rates for both premium and… Puerto Vallarta Gears Up for the 2024 Marathon Puerto Vallarta is abuzz with anticipation as it braces to host the fifth edition of its renowned Marathon, slated to kick off on April 21. This eagerly awaited sporting spectacle has firmly entrenched itself as a highlight on the global athletic calendar, drawing participants from diverse corners of the world. The 2024 Puerto Vallarta Marathon…

Puerto Vallarta Gears Up for the 2024 Marathon Puerto Vallarta is abuzz with anticipation as it braces to host the fifth edition of its renowned Marathon, slated to kick off on April 21. This eagerly awaited sporting spectacle has firmly entrenched itself as a highlight on the global athletic calendar, drawing participants from diverse corners of the world. The 2024 Puerto Vallarta Marathon… Cultural Clash: Complaints of Noise by Expats Spark Debate Across Mexico Puerto Vallarta, Mexico - In Mexico, the vibrant tapestry of culture is woven with the threads of music, celebration, and tradition. However, recent complaints from expatriates, primarily of American origin, have sparked a debate on the intersection of cultural identity and noise pollution. Mazatlán's Sinaloan Band Protest In late March, the boardwalks of Mazatlán, Sinaloa,…

Cultural Clash: Complaints of Noise by Expats Spark Debate Across Mexico Puerto Vallarta, Mexico - In Mexico, the vibrant tapestry of culture is woven with the threads of music, celebration, and tradition. However, recent complaints from expatriates, primarily of American origin, have sparked a debate on the intersection of cultural identity and noise pollution. Mazatlán's Sinaloan Band Protest In late March, the boardwalks of Mazatlán, Sinaloa,… Triple Arrival of Cruise Ships Brings Thousands of Tourists to Puerto Vallarta Puerto Vallarta, Mexico - On Tuesday, April 16th, Puerto Vallarta witnessed a bustling spectacle as three grand cruise ships made their way into its vibrant harbor, injecting the city with a surge of international tourists eager to explore this renowned beach destination. The trio of maritime giants included the Zaandam, gracefully docking at Pier 1,…

Triple Arrival of Cruise Ships Brings Thousands of Tourists to Puerto Vallarta Puerto Vallarta, Mexico - On Tuesday, April 16th, Puerto Vallarta witnessed a bustling spectacle as three grand cruise ships made their way into its vibrant harbor, injecting the city with a surge of international tourists eager to explore this renowned beach destination. The trio of maritime giants included the Zaandam, gracefully docking at Pier 1,… FAKE NEWS ALERT: American Reported Missing in Puerto Vallarta Found After Four Hours, Not Four Years Recent false claims circulating online regarding an alleged four-year disappearance of an American in the jungles of Puerto Vallarta have been debunked. The individual was actually reported missing on April 9 and found a mere four hours later, highlighting the swift and efficient response of local authorities in safeguarding the community. This incident underscores the…

FAKE NEWS ALERT: American Reported Missing in Puerto Vallarta Found After Four Hours, Not Four Years Recent false claims circulating online regarding an alleged four-year disappearance of an American in the jungles of Puerto Vallarta have been debunked. The individual was actually reported missing on April 9 and found a mere four hours later, highlighting the swift and efficient response of local authorities in safeguarding the community. This incident underscores the… Tryst Puerto Vallarta is the Area’s Newest LGBTQ+ Hotel Puerto Vallarta has long been hailed as the premier LGBTQ+ beach destination in Mexico, thanks to its vibrant community and array of tailored offerings. Bolstering this reputation is the recent unveiling of The Tryst Puerto Vallarta, a boutique hotel that not only promises lavish accommodations but also serves as a hub for guests to immerse…

Tryst Puerto Vallarta is the Area’s Newest LGBTQ+ Hotel Puerto Vallarta has long been hailed as the premier LGBTQ+ beach destination in Mexico, thanks to its vibrant community and array of tailored offerings. Bolstering this reputation is the recent unveiling of The Tryst Puerto Vallarta, a boutique hotel that not only promises lavish accommodations but also serves as a hub for guests to immerse… Possible Case of Measles Under Investigation in Puerto Vallarta The Jalisco Health Secretariat is investigating a potential case of measles in Puerto Vallarta, though no confirmation has been made yet. Head of the eighth health region, Jaime Álvarez Zayas, revealed this development, emphasizing that while it's being treated as a febrile exanthematic illness, it has been forwarded for thorough analysis. Álvarez Zayas stated, "A…

Possible Case of Measles Under Investigation in Puerto Vallarta The Jalisco Health Secretariat is investigating a potential case of measles in Puerto Vallarta, though no confirmation has been made yet. Head of the eighth health region, Jaime Álvarez Zayas, revealed this development, emphasizing that while it's being treated as a febrile exanthematic illness, it has been forwarded for thorough analysis. Álvarez Zayas stated, "A…