Mexico City — In response to a wave of illegal property takeovers plaguing the capital, authorities have unveiled a sweeping strategy to protect residents from “despojo” – the forcible or fraudulent occupation of homes. Mayor Clara Brugada this week presented legal reforms that would sharply increase prison sentences for property squatters and their enablers, while closing loopholes that have allowed criminal groups to dispossess homeowners with impunity. The crackdown comes as officials reveal startling figures: more than 2,245 investigations of property theft have been opened in Mexico City so far in 2025, with organized bands often targeting the elderly and other vulnerable owners.

“Property despojo has become a cancer in our city, one that leaves families homeless and intimidated,” Brugada said at a press conference in the historic Zócalo plaza. Flanked by the city’s justice and security chiefs, she announced an “Estrategia Contra Despojos” (Strategy Against Property Grabs) that combines tougher laws with dedicated enforcement. Under the proposal, the base prison term for the crime of despojo will rise from the current 5–10 years to 6–11 years, and in aggravated cases, the maximum penalty will double from 11 to 22 years, with no right to bail for those severe scenarios. Aggravating circumstances include if violence or threats are used, if public officials or notaries are involved in the fraud, or if the victims are elderly, minors, or disabled – all common elements in real-world cases.

The reforms also expand the definition of the crime. Refusing to vacate a property despite a court order – a tactic some squatters have used to drag out cases – will itself become a criminal offense, equated with despojo. Additionally, the law will explicitly cover those who use false legal documents or abuse legal processes (like fake wills or sham lawsuits) to seize someone’s real estate. “No more hiding behind paperwork or procedural tricks. If you take someone’s home illegally, you will face consequences,” warned Mexico City Attorney General Ernestina Godoy.

Statistics presented by officials underscore the urgency. In the first half of 2025 alone, 2,245 criminal complaints for despojo were filed in Mexico City. Authorities managed to secure 265 properties from occupiers, of which 196 have been restored to their rightful owners so far. Many cases remain tied up in court, however, or are awaiting action. The city recently set up a special help desk in the central square to receive despojo reports – it logged 150 cases in its first three weeks of operation. Each case often involves heartbreak: families terrorized by mafias, life savings lost, and inheritance disputes exploited by scammers.

The modus operandi of these property raiders varies. Some groups use outright violence and intimidation, essentially storming a home and kicking out the occupants at gunpoint. Others deploy more subtle white-collar tactics: forging deeds, bribing corrupt notaries to create fake property titles, or initiating simulated legal suits to claim ownership. Often, multiple actors are involved – a lawyer, a notary, perhaps a complicit public registrar – amounting to what officials call “delincuencia organizada de cuello blanco” (white-collar organized crime). These networks frequently prey on the defenseless: elderly owners who live alone, heirs of a recently deceased homeowner who haven’t sorted the paperwork, or marginalized communities without formal land titles. “They operate via threats or via fraud, but the result is the same – families left on the street,” said Jorge Aguilar, head of the city’s legal department.

The anti-despojo plan goes beyond penalties. Mayor Brugada outlined complementary administrative reforms to choke off the fraud routes. One measure will require any out-of-state notary public who wants to notarize a property transaction in Mexico City to first obtain a certification from local authorities. This is aimed at curbing a known trick where unscrupulous notaries from other states (with looser oversight) issue documents used to claim Mexico City properties. Another change will empower the Public Property Registry to place precautionary alerts on properties that appear to be targeted by fraud, and to create electronic notifications so rightful owners get warned if someone tries to tamper with their title.

Additionally, the city’s Attorney General’s Office announced it will create a specialized unit to investigate despojo. Currently, these cases are handled by a division that also covers environmental crimes, diluting focus. The new unit will have dedicated prosecutors and investigators, plus criteria to prioritize cases involving violence or vulnerable victims. By analyzing patterns, they aim to dismantle entire rings. Already, the city has had some success: last year, a joint operation with federal authorities busted a ring known as “Los Cerebros” that had fraudulently taken over at least 15 properties using forged wills and ID theft. Members of that ring are now on trial.

Victims and advocacy groups have welcomed the initiative. At the press conference, Brugada was joined by citizens holding signs that read “No más despojos” (No more dispossessions). Among them was 85-year-old Doña Ernestina, who bravely recounted how a group of strangers showed up at her Coyoacán home in 2022 claiming it was theirs, armed with a bogus deed. They harassed her and even tried to change the locks. It took a year and a court battle – during which time she had to live with relatives – before a judge finally ruled in her favor and evicted the interlopers. “They stole a year of my life,” she said, voice quavering. “I don’t want anyone else to suffer that.” She believes if the new law had been in place, the perpetrators would have thought twice, and the police could have acted faster.

Not everyone is convinced that harsher laws alone will fix the problem. Some legal experts caution that Mexico’s judicial system is slow, and stiff penalties might mean little if cases drag on for years. They urge bolstering mediation and administrative remedies to resolve property disputes quickly before they escalate. In response, officials point to parallel efforts: the city is expanding free legal aid to help vulnerable owners manage their paperwork (like updating deeds and wills) to make them less susceptible to fraud. Campaigns to raise awareness are also planned, advising people not to sign documents under pressure, and to verify any supposed court orders or notary notices with authorities.

Mayor Brugada emphasized that these measures have teeth thanks to coordination with federal lawmakers. She noted that members of Congress from Mexico City’s delegation intend to push similar reforms at the national level, since despojo isn’t just a capital problem – other states like Morelos and Jalisco have seen a rise in such crimes, too.

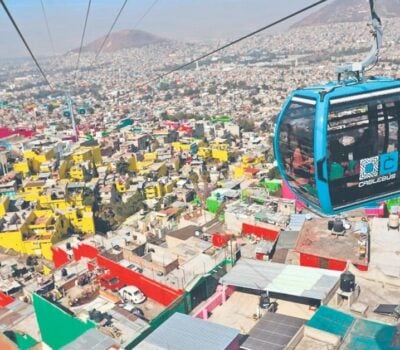

The crackdown in Mexico City is part of a broader trend of protecting citizens’ property rights. It follows high-profile actions like the government’s seizure and return of nearly 200 illegally occupied apartments in a downtown complex earlier this year, and efforts to regularize land tenure in poorer neighborhoods.

For now, families like Doña Ernestina’s feel a glimmer of hope that justice will be swifter and harsher for those who try to steal homes. “If this law had existed, those people who took my home would be in jail,” she said. “I sleep better knowing others might be spared what I went through.” The city has sent a clear message: the era of easy home grabs in Mexico City is coming to an end.